The family man

By Antonio Nicaso / Toronto Life

IN THE EARLY MORNING OF JULY 15, 1998, residents of Goldpark Court in Woodbridge were astonished to see that their street had been turned into a parking lot for police cars. One of the cruisers blocked the entrance to the cul-de-sac, cutting off a dozen media vehicles. Several reporters left their cars and hopped fences down the block.

At 7:07 a.m., a member of the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit rang the doorbell at 38 Goldpark Court. Alfonso Caruana's wife, Giuseppina, let the officers in. Upstairs in the hallway, they found a bleary-eyed Alfonso, in shorts and T-shirt. He was handcuffed, read his rights in English and Italian, and allowed to inject his leg with insulin. His nephew Giuseppe, visiting from Montreal, was also arrested.

Downstairs, Giuseppina Caruana fixed her husband some toast, a grapefruit and half a cheese sandwich. After he said goodbye, an RCMP officer told him reporters were waiting outside. "Do you want to cover your head?''

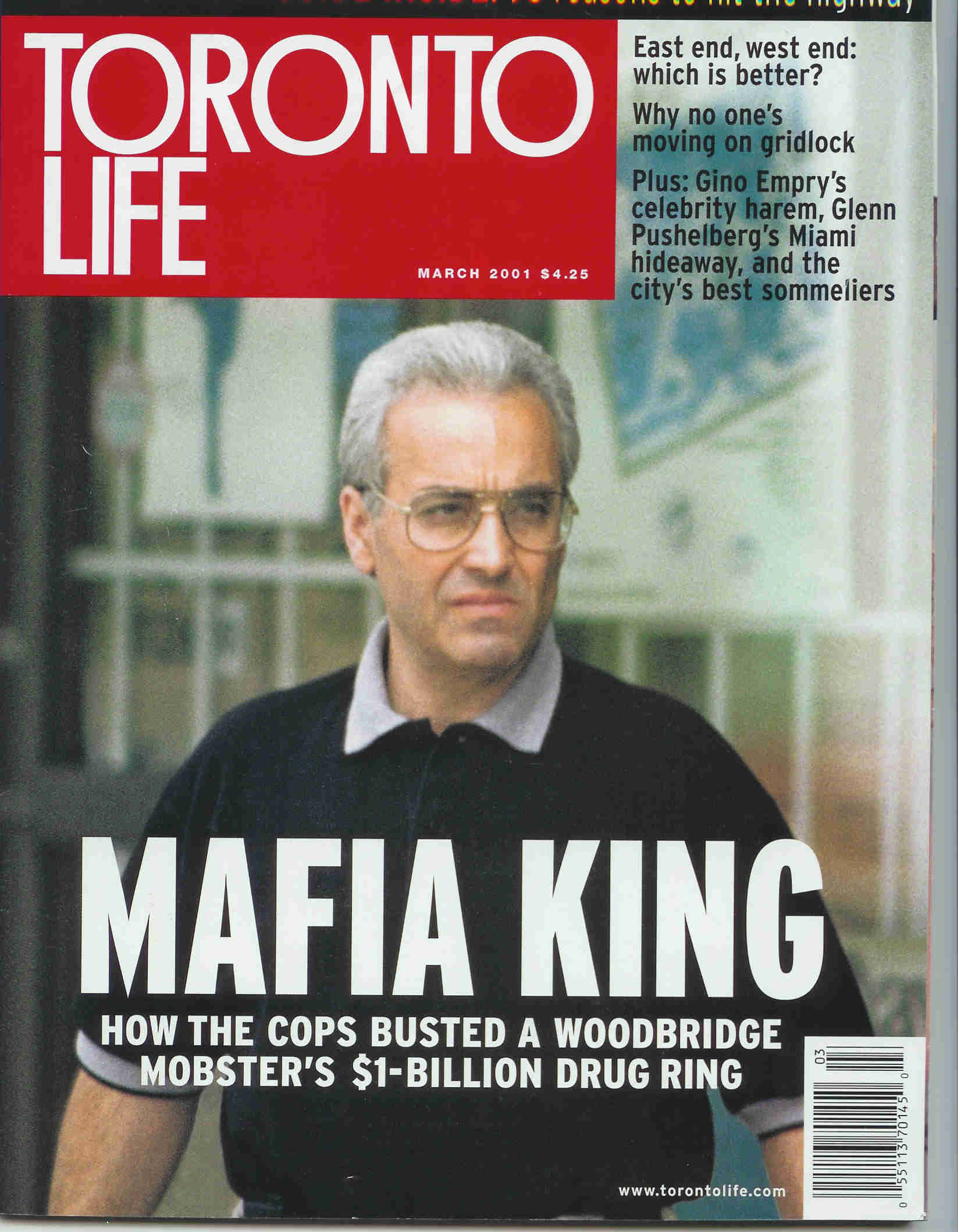

"I don't care,'' Caruana shrugged, and stepped into the media spotlight he had avoided during a lifetime that had seen him rise from humble origins in the village of Siculiana, Sicily, to leadership of one of the biggest drug-trafficking and money-laundering organizations in the world.

In Italy, Caruana had already been convicted in absentia of international drug trafficking. The Palermo Court of Appeal had upheld the sentences against him and a dozen other members of the Caruana-Cuntrera family. Alfonso had been sentenced to 21 years, 10 months.

Until 1995, he was believed to be living in Venezuela, one of many South American countries in which the Caruana-Cuntrera had extensive interests. But in June of that year, he made an appearance, every inch the proud father, at his daughter's wedding reception at the Sutton Place hotel. Law enforcement officials were monitoring the event. They soon discovered that one of the world's most wanted men was living quietly in Woodbridge, and Project Omerta (named after the Mafia code of silence) was born. Its mandate was to bring charges against the leaders of the Caruana-Cuntrera.

Late in 1997, the Omerta team--made up of RCMP, OPP, Toronto and regional forces--took a big step toward that goal when it cracked the code used by the Caruana-Cuntrera for phone numbers. Each digit was adjusted to add up to nine: one became eight (8+1=9), three became six (3+6=9), and so on. With that knowledge, the squad was able to gain extraordinary insight into the family's worldwide workings.

The nerve centre of the organization turned out to be a building on Duffering, which housed the Shock Nite Club and Autobahn Car Care, where Caruana was on the books as an employee. He drove his gold Cadillac there each day before circling around to a variety of phone booths to make his business calls. Caruana, of course, believed the pay phones were secure, but police were gathering intelligence--who was travelling where, business schemes, the corruption of bank employees, government officials and politicians. Caruana and Oreste Pagano--a Naples-born Mob boss who operated out of Venezuela, Mexico and Miami--were making specific drug and money transport arrangements. By late 1997, Omerta had compiled reams of evidence against Caruana. But one thing was missing from their case: drugs.

ON JANUARY 2, 1998, the day after Caruana's 52nd birthday, Omerta got word that a load of cocaine--hundreds of kilos--was ready for shipment from Colombia via Venezuela to Canada. Oreste Pagano left his coded number on Caruana's pager. A few minutes later, Caruana, on what he thought was a safe line, called to say, "Everything's OK, thank God.''

"When is he leaving?'' Pagano asked.

A courier would bring cash down to him and return to Canada with the drug shipment.

"We'll see this coming week,'' Caruana replied.

He then got his brother Gerlando, who ran the Montreal operation, to contact a man who was often used to arrange couriers for the family, its de facto customs broker.

A couple of weeks later, Caruana and a companion were observed driving into the parking lot of Longo's supermarket on Weston Road. They got out of a white Chevrolet Malibu, Caruana going into the store, his companion leaving the keys in the car and walking off in another direction. Within minutes, another man--the family referred to him as the "big guy''--climbed into the car and headed for the 401 east.

Caruana called Montreal. "Listen, the big guy is leaving now. Understand? From seven to 7:30, have someone be there [to meet him]. And tomorrow morning you meet again.''

Next morning in Montreal, the big guy met with three men. He handed over the car keys. When the Malibu was returned to him a few minutes later, he drove back to Toronto, keeping his speed to a sedate 95 to 100 kilometres per hour. At his home in Richmond Hill, he removed a plastic bag and a large cardboard box from the trunk and took them inside.

The money he had taken to Montreal--$1.5 million cash--was in turn driven by couriers to Miami. But somewhere along the line, the $1.5 million had become $1.4 million. Pagano, apprised of the shortfall, called Caruana.

"It's one four.''

"It's one four?''

"Yes.''

"No.''

"Yes.''

"It's one five, not one four,'' Caruana assured him.

"It's precisely one four.''

"Fuck, this situation is driving me nuts now.''

Pagano said the same person did the count each time in Miami: his son, Massimiliano. Caruana said his brother Gerlando did the count before the money left Canada. "Now we have to see how the fuck...we have to find these fuck-ups.''

The next day, Caruana reached his nephew in Montreal. ``Listen, how much did you give that guy? One four or one five?''

"One five.''

"Because that guy says it's one four.''

"No. I sent one five.''

"Now we have to see who the fuck is not telling the truth.''

In their next conversation, Caruana gave Pagano a breakdown of the cash shipment: "There was 730,000 in twenties, 440 in hundreds, and 330 in fifties.''

Who stole the money was never determined. Some thought it was the family's customs broker; others thought it was one of the younger Caruanas in Montreal. Others thought Pagano and his son cut up the $100,000. In any case, Oreste Pagano reached into his own pocket to make up the difference.

IN PAGANO, ALFONSO CARUANA had a reliable offshore connection with access to major suppliers. Caruana was in almost constant need of drug shipments, not only for Canada but also for Italy. On February 16, 1998, he again called Pagano. Police activity in Toronto was heating up, and Caruana didn't have the freedom to move as quickly as Pagano wanted.

"Send me some green,'' Pagano urged from Venezuela.

"I don't know, Compa. It'll be difficult.''

"Because I have to pay those people. Otherwise, we'll lose a lot of money in the exchange.''

"It's difficult, it's difficult. The situation is a little critical here. I can't move around as much as I could a while back, you understand me? There is more pressure than ever.''

Caruana, though under surveillance, practised only rudimentary evasion. He drove to Shannonville, Ontario, where he picked up a duffle bag from the home of a childhood friend. His nephew Giuseppe came to Toronto and took bags of cash back to Montreal. Before long, another load of money was ready to go south.

But there were problems. One courier broke his leg and couldn't drive; the customs broker couldn't get a team together until the following month. Some problems were ridiculously mundane: when the broker went to pick up the cash, Gerlando and Giuseppe Caruana could find only a small ``purse'' to hold it. Giuseppe suggested going to the local Price Club, but it was about to close, and the money transfer was put off till the next day.

Caruana and Pagano talked finances. For 500 or 600 kilograms of cocaine, they would pay, after shipping and expenses, $16,000 per kilo. Each kilo would sell for up to $35,000 in Canada. Each man had to put up about $3.5 million cash. They'd split a profit of perhaps $12 million.

A few days later, Pagano told Caruana he wanted to increase the size of the shipment. They'd pay half up front. His suppliers wanted to know how soon he'd pay the rest. Caruana was incredulous; he didn't like Colombians, and Pagano's latest supplier in particular.

"What do you mean, pay ahead of time! Compa, what kind of reasoning is this? What if it doesn't arrive?''

"If it doesn't arrive, they'll give me [back] the money.''

"One cannot pay for it before it arrives. Fuck, how do these people work? I don't know. I have never heard of this being done.'' He told Pagano the next cash shipment was for only $80,000. Pagano groaned. "Compa,'' said Caruana, "please don't be like that. You don't know all the problems I have here, the difficulties.''

Early in March, Pagano informed Caruana: "Next week, the architect will be leaving for where the little boy is, you know?''--meaning the cocaine would arrive in Miami, where Massimiliano was. He needed the cash so that both the money and the drugs could be quickly moved.

Later it became clear that two shipments were being planned: one for Caruana and another Mafia family; the other for Caruana, Pagano and a Colombian distributor. One shipment was in Mexico City and would go to Miami. Drugs were backing up in Florida, awaiting distribution. The plan was to move the cocaine to Canada in lots of 100 kilos.

In Montreal, the customs broker lined up couriers. He called an associate named John Hill in Sault Ste. Marie and had him come to Montreal for a briefing. Hill, accompanied by another courier, Richard Court, drove back to Sault Ste. Marie, followed by the broker and his gofer, in a sedan. On April 19, both vehicles--Hill in his pickup truck; Court, the broker and his gofer in the sedan--crossed into the States.

Hill's pickup was flagged by the U.S. customs computer, and he was pulled over for a level two check. But an Omerta member was able to alert U.S. customs that Hill was under surveillance; he was allowed to pass. Both vehicles set off for Florida and were followed all the way to Miami.

JUST BEFORE NOON ON APRIL 21, Oreste Pagano called Caruana: "I'm really worried, because Willie [their code name for Alberto Minelli, a globe-trotting money man] said there are people following him.'' Pagano said his son was at Minelli's house with the money. "They can't be moved.'' With that shipment frozen, talk turned to the second shipment: 200 kilos of cocaine, 150 for Caruana and Pagano, the other 50 for the Colombian distributors.

"Compa, I'm completely broke. I gave everything I had...''

"There is no need for me to give the money. For the first time, they will give it to me.''

Later Pagano called again: the money still couldn't be moved from the Miami house. Without it, the cocaine couldn't be picked up. Pagano said the "stuff is well hidden but can't be moved. We'll wait a week and then do it.''

When word of the "burn'' on the surveillance outside Minelli's house reached Larry Tronstad, an RCMP staff sergeant, he called the FBI. It wasn't them, the FBI claimed. "Bullshit,'' Tronstad replied. "They've got everything: the make and colours of your cars, everything but the licence plates.''

The agent called back to say that, indeed, a "renegade surveillance team'' had set up at Minelli's. They were being pulled out. But it was too late for the Omerta team to catch their suspects with the drugs. The transaction had been aborted.

IN FLORIDA, THE TWO COURIERS, Hill and Court, were getting antsy. "These guys here told me it's useless,'' the customs broker explained to Gerlando Caruana in Montreal. "They've lost faith in me, you understand? They've lost trust in me; this is the problem.'' To cool them down, the broker gave them each $1,500 for expenses. Hill accepted it--he was also getting free cocaine to keep him quiet--but the other courier was angry. The broker had deducted $560 Court owed him. Court refused to accept the balance.

Needing Hill, if not Court, for an upcoming Houston drug run, the broker worked him. "John, listen, I like the way you act, that you work. Now, I want you to think about...we have problems with this guy. He's nervous, he's paranoid, he's really unreliable. Anyway, think about it, and we gonna talk after.''

Hill and Court wanted nothing to do with the run to Texas, but their boss muscled them. After the problems in Miami, he told them, the Houston run was critical for the family. He persuaded them with five words: "You're playing with your lives.''

Tronstad wasn't taking any chances. He decided to install a global positioning satellite in Hill's pickup. GPS requires a clear line of sight to an orbiting satellite and a space large enough to hold batteries, so Tronstad's team scouted a hiding place on a similar truck. Once the couriers had returned to Canada, Tronstad sent his crew to Hill's home in Sault Ste. Marie. Under cover of darkness, with the neighbour's dog barking in the background, they installed the device.

ON MAY 15, PAGANO PHONED Pasquale Caruana, another of Alfonso's brothers, to confirm the Houston shipment: "The documents have already been handed over.''

"That's fine,'' said Pasquale.

The next day, the broker, his flunky and the couriers were in Houston, ready to make the run. With Court and Hill in the pickup-- "loaded to the roof,'' as Hill later said--they headed back toward Canada. Court later said he knew the shipment was doomed. "I thought Texas was a hot spot; I thought that the timing was rushed; I thought the preparations were forced...It was almost like not even concealing [the drugs]... throwing them into the vehicle.''

An hour outside Houston, state troopers pulled Hill over for an improper lane change. They smelled a strong chemical odour and noticed a sleeping bag draped over several bulky items in the back. The truck contained 11 bags of cocaine, 200 kilograms. At last, Project Omerta had its "powder.''

The broker and his gofer had driven right by the arrest. They found an off-ramp and turned back for a second look. Believing themselves in the clear, they continued on to Canada. "We let them go,'' Tronstad said. ``It would look to Alfonso Caruana that the lost load was just the cost of doing business. We were hearing they were planning loads from California, and we didn't want to spook them.''

ORESTE PAGANO, meanwhile, had moved from Caracas to Cancun, where he was working out of a real estate office. Protection could easily be bought in Cancun. The rule of thumb was that if an official turned down a bribe, it was only because he or she had already been bought for a larger sum. Pagano's influence reached the highest level: the governor of the state of Quintana Roo. Mario Villaneuva was key to the success of many drug traffickers. He reportedly took tens of millions of dollars from Mexican cartels. A much sought-after service he offered was the use of government aircraft hangars as transfer points for cocaine shipments.

One of Villaneuva's intimates was Alcides Ramon Magana, a leader of the Juarez cartel. On June 2, 1998, a young Mexican army lieutenant--part of a secret CIA-trained anti-drug task force--who was investigating links between Villaneuva and Magana stopped at a traffic light. His vehicle was surrounded by cops, who dragged the lieutenant out at gunpoint. He was turned over to Magana's cartel and tortured, while other cartel members broke into his office and looted it of documents tying Villaneuva to the drug trade.

When word of the kidnapping reached the Mexican minister of defence, he sent soldiers, backed by armoured personnel carriers, to Magana's home in Mexico City, trapping his wife inside. Magana was told that unless the lieutenant was freed, the convoy would open fire on his house. Meanwhile, black-clad commandos were sent into the enclaves of the wealthy drug traffickers to hunt for the lieutenant. Yielding to the pressure, the cartel finally released him.

In Toronto, Larry Tronstad monitored events with trepidation. "The Mexicans were going nuts,'' he said. "They were going to raid the homes and businesses of every suspected drug dealer in the province.'' He was worried that Oreste Pagano would be included in the roundup. On top of it, he knew that American police were pushing for Pagano's arrest in another investigation. Tronstad conferred with superintendent Ben Soave, head of the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit. Soave in turn called a contact in Italy, who persuaded the American police to back off. Together, they managed to keep Project Omerta alive.

IN WOODBRIDGE, ALFONSO CARUANA knew police were closing in. His greatest fear wasn't being arrested--he had, after all, the rights of a Canadian citizen--but being extradited to Italy. Meanwhile, he had a new shipment to attend to. He had 500 kilos of cocaine en route to Canada by ship.

Pagano had gone out on a limb with this shipment. Caruana, feeling the heat, hadn't wanted to expose himself by gathering cash, so Pagano had put up the entire down payment himself: about $750,000 (U.S.).

On June 5, 1998, The Hamilton Spectator carried a frontpage headline: CANADIAN HAVEN: ALLEGED MAFIA BOSS LIVING QUIETLY NEAR T.O. Several reporters had learned about Caruana but, urged by Soave, had agreed to hold the story until his arrest. After an Italian newspaper quoted a Mafia investigator as saying, "We have reason to believe [Alfonso Caruana] is hiding in Canada,'' Adrian Humphreys of the Spectator located Caruana's home on Goldpark Court.

But even before the story broke, Caruana had been working on an exit strategy. Italian police knew he'd been in contact with a master Iraqi forger. They raided the man's home at 4:30 a.m., seizing documentation, perfectly forged, and four cellphones.

"If I were you, I know what I'd do,'' Pasquale Caruana told the Iraqi forger over the phone. "Right away, right away,'' he continued. "Just leave right away, understand me?''

The Iraqi said he'd go to Holland and call from there. He said he'd have false passports ready within days. Clearly, Alfonso Caruana was planning to flee Canada. Soave began making plans for the takedown.

In July, Caruana made it clear to Pagano that he expected to be arrested. "Compa, you wouldn't believe it. I'm being watched 24 hours. I don't call, because these bastards are following me. As soon as I hang up the phone, they're checking to see who I call and who I don't call.''

Pagano, understandably, was anxious about the 500-kilo shipment he had paid for. He sent pager messages to Caruana in Toronto but received no callback. He phoned Caruana's lawyer in Montreal and asked if Alfonso had been arrested. No, everything was fine. Pagano then called Gerlando Caruana, who said all was well: the shipment had arrived.

THE OMERTA RAIDS were set for dawn on July 15. Arrests in Toronto, Montreal and Cancun were to be made at precisely seven a.m., Eastern Standard Time. But in Cancun, four hours before the appointed time, dozens of officers smashed into Pagano's bedroom. It was his 60th birthday.

"Oreste, Oreste, how are you?'' said one. "Happy birthday.''

"We'd asked them to hold off until seven a.m., to secure his office,'' said Tronstad. "We wanted to get into the safe, and we wanted to seize the hard drive from Pagano's computer. We believed there was a lot of money in the safe, and the computer could provide sensitive information about drug-trafficking and money-laundering operations.''

When officers arrived at Pagano's real estate office, however, they found members of Mexico's anti-drug squad wearing Royal Mott Real Estate T-shirts and consuming Pagano's supply of beverages and food. The floor safe had been drilled open, its door left ajar. It was later determined there had been as much as $800,000 in cash and jewellery in the safe. The computer was also gone.

The Mexican officers were the pride of American anti-drug foreign policy. All had been hand-picked for bravery and honesty, undergone extensive training and been given polygraph tests. After the raid, all were transferred to other duties.

WHEN LARRY TRONSTAD learned that Pagano had already been arrested in Cancun, he scrambled to get a team to Alfonso Caruana's home in Woodbridge. If word got out, he feared, Caruana would bolt.

Besides the arrests that morning at 38 Goldpark Court, simultaneous raids were carried out at, among other places, Pasquale Caruana's home in Maple, Gerlando Caruana's home in Montreal, and the Shock Nite Club on Dufferin, where $200,000 was found hidden in the ceiling.

Caruana hired John Rosen, famous for his unsuccessful but blistering defence of Paul Bernardo. Rosen, who had defended other organized-crime figures, was later replaced by Pierre Morneau from Montreal. Pasquale Caruana hired Marlys Edwardh, who blitzed the prosecutors with so many challenges, requests for translations, tapes, documents and other items for disclosure that Tronstad wrote sarcastically in a memo: "I wonder, does she know she forgot to get DNA samples from all the officers involved?'' Months of wrangling ensued. Meanwhile, John Hill and Richard Court both turned informant in Houston, making deals with the U.S. government in exchange for full statements.

Pagano, flown in from Cancun, tried to get enough money to hire a decent lawyer. In letters to his common-law wife, he urged her to use "any means possible'' to prevent his extradition; he figured he was facing only three or four years of incarceration in Canada. Caruana still owed him for the 500-kilo shipment to Montreal. At the Metro Toronto East Detention Centre, Pasquale Caruana told Pagano to relax: "Don't worry. We'll [see] if we can get something to arrive.'' Gerlando Caruana was there, too. "We'll bring in more and make it all back,'' he said. "We're not talking about 500 grams,'' Pagano replied. "We're talking about 500 kilos.''

The Caruana brothers, he said, discussed helping him escape, but he grew disillusioned. He knew that other members of the Caruana-Cuntrera family were already distributing the last cocaine shipment, collecting the money. Including Caruana's portion of the latest shipment, he was owed $7 million (U.S.).

One morning in November, when Pagano approached Gerlando and Pasquale at the detention centre, they shunned him, believing he was talking to police. By lunchtime that day, he was. He wanted to make a deal, he said, "a patch.'' He could give police the entire organization. In return, he wanted his wife brought under guard from Venezuela, a new identity, a place to live with his family, and the money and assets seized by Mexican authorities returned to him. He also wanted to be moved from Metro East. He wanted his sister and her children in Italy protected. And he wanted Alberto Minelli excluded from prosecution.

When he was asked what information he had to offer, Pagano said he could outline narcotics networks in Italy, the States, Canada and Colombia. He could show a total of 10 tons of cocaine that had moved through Caruana's network. He described a 5,500-kilogram shipment to Italy, the way containers were used to smuggle cocaine into the States, and his contacts in the Mexican cocaine cartels.

After months of negotiations, Pagano cut a deal whereby the police "loaned'' him $25,000 for legal representation. His lawyer ultimately negotiated protection for Pagano's family, a place in Italy's witness protection program and $100,000 for his cooperation. On December 7, 1999, Pagano pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to import cocaine. He got one day in jail, and was put on a plane to Italy the next day. If needed, he would return to testify against the Omerta suspects.

In Italy, Pagano is providing information expected to lead to the resolution of several homicides, including the murders of police officials. He has turned over his Colombian drug supplier, who is also cooperating with authorities. Married to the daughter of a Colombian general, the man is expected to reveal a network of drug trafficking that reaches as far as Russia. He admitted he himself moved 75 tons of cocaine, much of it to the Caruana-Cuntrera family, over 12 years.

Among Pagano's assets was a millionacre parcel of mineral-rich land worth tens of millions of dollars. In cutting his deal, he signed the property over to the Canadian government, which is now negotiating with Venezuela over ownership.

AS IT TURNED OUT, Oreste Pagano's testimony was not needed to convict Caruana. On February 25, 2000, facing Pagano's betrayal, a mass of police evidence and the prospect of being extradited even if he managed to beat the Canadian charges, Caruana also pleaded guilty to count of conspiracy. He got 18 years and is serving his time in a medium-security prison north of Toronto.

Alberto Minelli was extradited to Italy to face money-laundering charges. Caruana's Montreal nephew, Giuseppe, was sentenced to four years and was recently paroled after eight months. Pasquale and Gerlando got 10 years and 18 years, respectively, both for conspiracy to traffic narcotics. In all, some 50 people were investigated during Project Omerta.

Police knew of at least 14,000 kilograms of cocaine moved by Caruana-Cuntrera--they seized only 200. Omerta cost an estimated $8.8 million. The financial returns were relatively meagre: $623,578 in jewellery, $622,000 in cash, $585,000 in bonds. That just about covered the cost of translators.

Alfonso Caruana left various deals in the works; the Caruana-Cuntrera family carries on its dark global business without his leadership. Omerta may have effectively removed a generation from the organization, but soon after Caruana's guilty plea, others had stepped forward to stake their claim to power.

May 2001